Cognitive Dissonance and Climate Change

- Instructor Prep: 2 hours | Seminar: 1-2 class slots

- Keywords: Beliefs | Behaviours | Confirmation Bias

INTRODUCTION

This teaching guide is meant to seamlessly fit into existing lesson plans in psychology courses, in this case lessons on cognitive dissonance. This guide links how cognitive dissonance can play a large role in the emotions we experience in the face of climate change and the implications of avoiding it.

COGNITIVE DISSONANCE

Cognitive dissonance describes a mental discomfort or tension that a person experiences when they hold two or more contradictory beliefs, values, or attitudes at the same time. This discomfort often arises when a person’s behaviour contradicts those beliefs or values. For example, if a person knows that flying is harmful for the environment (belief), but they continue to take holiday trips around the globe (behaviour), they may experience cognitive dissonance. To reduce this discomfort and restore balance, individuals may alter one of the conflicting attitudes, beliefs, or behaviours over time. They may also try to justify or rationalise their behaviour, reject or avoid new information that conflicts with existing beliefs (confirmation bias and selective perception), or feel guilt or regret about past actions.

Cognitive dissonance theory, proposed by Leon Festinger in 1957, suggests that we have an inner drive to hold all our attitudes and behaviour in harmony and avoid disharmony. When there is an inconsistency (dissonance), something must change to eliminate the dissonance. The concept is key to understanding humans’ behaviour about sustainability topics, where beliefs and behaviour often clash.

CLIMATE CHANGE

The main sustainability concept for this teaching guide is Climate Change. Climate Change refers to long-term shifts in the typical weather patterns that characterise Earth’s local, regional, and global climates. These changes, which encompass a wide range of observed effects, are driven primarily by human activities, particularly the burning of fossil fuels. This action increases the levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in our atmosphere, resulting in a rise in Earth’s average surface temperature. Natural processes, such as El Niño circulations also play a role but are much smaller than human driven climate change.

Scientists use observations from ground-based, airborne, and space-based platforms, in combination with computer models, to monitor and analyze past, present, and future climate changes. The result is a clear picture of different climatic changes from rising global land and ocean temperatures, to increasing sea levels and extreme weather. Climate change impacts many areas of our lives including health, food production, housing, safety, and employment. Climate Change is the biggest challenge of our and future generations.

For ease, we have developed several videos that provide basic information on these issues which can be assigned to students. These videos explain the following:

Local Actions Videos

CONNECTING THE DOTS

Cognitive dissonance plays a significant role in how people perceive and respond to climate change. There are many examples of this, including:

- Someone who is concerned about climate change, yet still flies for business may justify it to themselves by compartmentalizing their concern for the environment and their work, reducing their cognitive dissonance.

- A person who is very politically engaged may identify with a political ideology that has linked their outlook to denying or downplaying climate change. They may also deny or downplay climate change to maintain the consistency with their personal and political beliefs.

- An individual who is focussed on reducing consumption may experience cognitive dissonance when purchasing something they want.

- Someone may eat meat even if they are concerned by climate change and the high emissions from animals. They might rationalise this by thinking that dietary preferences are deeply ingrained and so cultural that they couldn’t possibly change.

- Cognitive dissonance can work in reverse. For example, within groups that may deny climate change, people may experience cognitive dissonance when experiencing extreme weather events. This drives a tension between their lived experience and their belief that climate change is not happening.

LOCAL ACTION AND IN CLASS ACTIVITES

- Have students speak to a family member, friend or colleague outside of the study about climate change. The aim is to discuss their concerns, hopes and philosophy on the topic. The conversation is not supposed to convert or convince people, but to analyse their way of thinking and identify cognitive dissonances.

- Students write a reflection consisting of a short summary of the person they spoke with, an analysis of their thoughts on climate change and a personal reflection on how the conversation went.

- A handout that can be provided to students is available in the download section

In class activity duration: 30 minutes

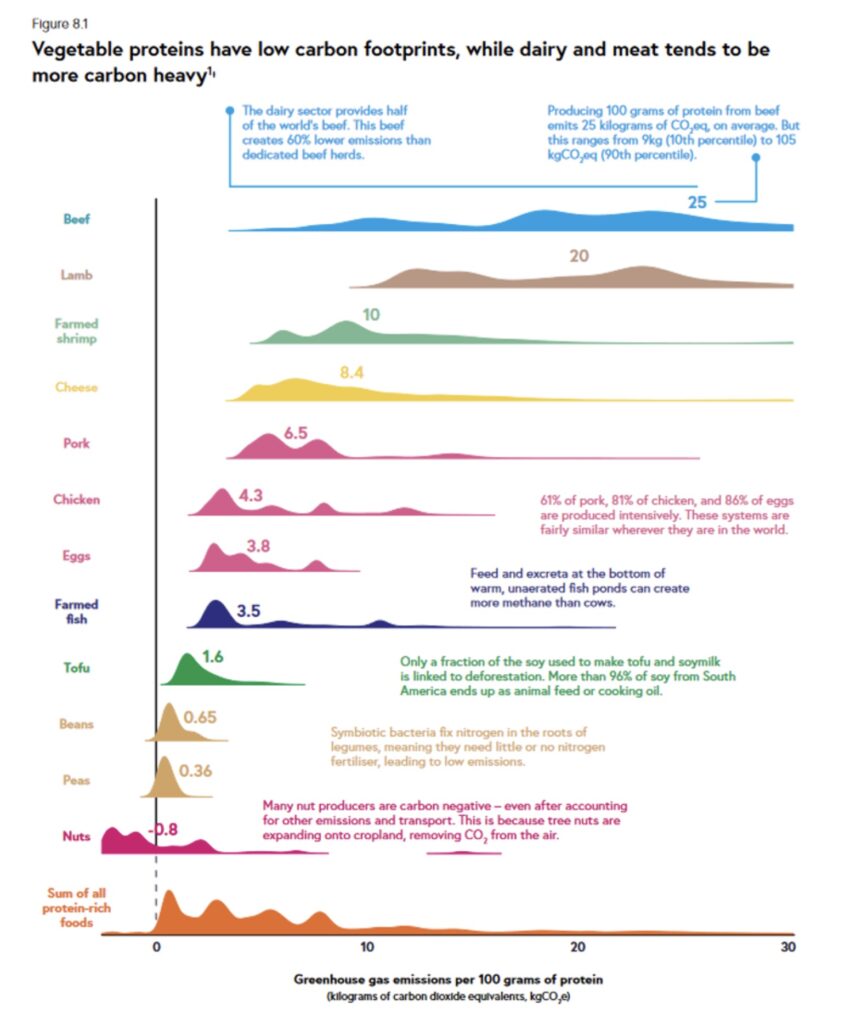

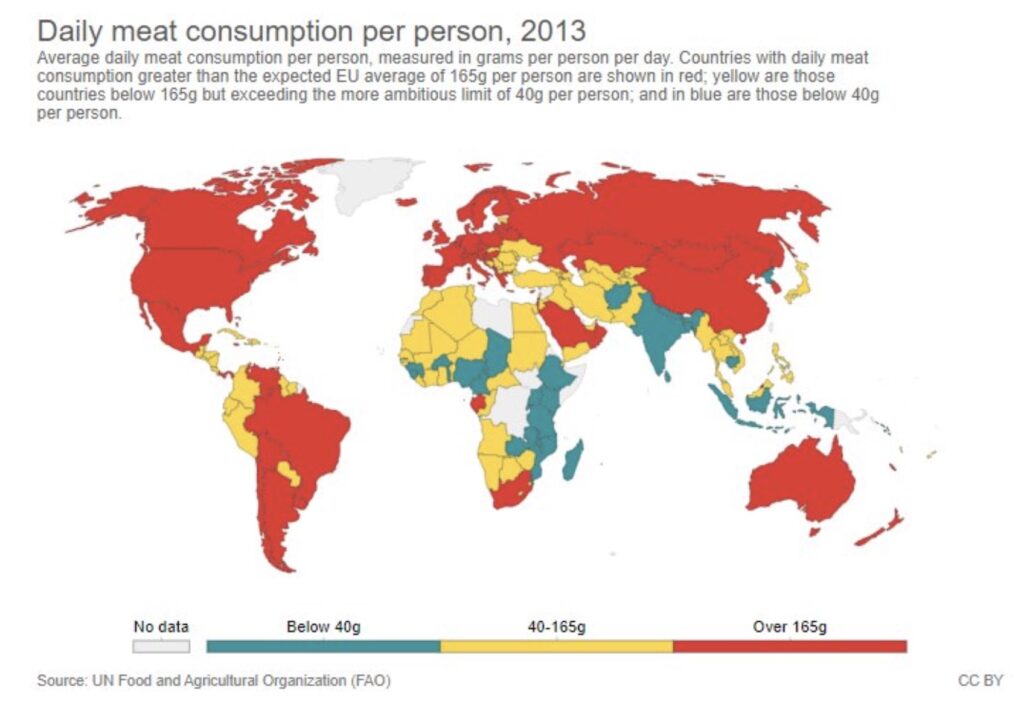

- Introduce students to two important figures on food emissions. First show the students an image of emissions from different food types (first image below) and then a figure of global meat consumption (second image below).

- Divide students up in groups and ask them identify explanations for the gap in intention and actions. Many of the high-income nations committed to reducing emissions are the largest consumers of meat. Good examples of rationalising to ease cognitive dissonance include: tradition, habits, personal taste, meat as a status indicator etc. Ask them to identify the different arguments that people may identify with for not reducing their consumption of meat.

- Different groups present their findings to each other and link it to the cognitive dissonance theory.

In class activity duration: 20 minutes

- Students get back into the same groups and are tasked with using what they learned about cognitive dissonance theory to come up with solutions to reduce meat consumption.

- After the brainstorm session, carbon labels can be introduced as an example. There are two studies that may be useful to reflect on referenced below including Shewmake et al (2015) and Apostolidis and McLeay (2019).

REFERENCES

Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (2019). An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. In E. Harmon-Jones (Ed.), Cognitive dissonance: Reexamining a pivotal theory in psychology (2nd ed., pp. 3–24). American Psychological Association.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Maiella R, La Malva P, Marchetti D, Pomarico E, Di Crosta A, Palumbo R, Cetara L, Di Domenico A and Verrocchio MC (2020) The Psychological Distance and Climate Change: A Systematic Review on the Mitigation and Adaptation Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 11:568899

Shewmake, S., Okrent, A., Thabrew, L., & Vandenbergh, M. (2015). Predicting consumer demand responses to carbon labels. Ecological Economics, 119, 168–180.

Apostolidis, C., & McLeay, F. (2019). To meat or not to meat? Comparing empowered meat consumers’ and anti-consumers’ preferences for sustainability labels. Food Quality and Preference, 77, 109–122.

https://edition.cnn.com/2017/04/20/us/louisiana-climate-change-skeptics/index.html